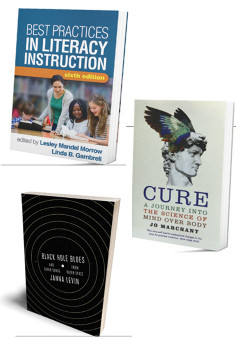

BEST PRACTICES IN LITERACY INSTRUCTION

BEST PRACTICES IN LITERACY INSTRUCTION

Lesley Mandel Morrow & Linda B Gambrell (Guilford Press)

Best Practices in Literary Instruction is a large-scale compilation of summary and descriptions of the current research, theory and practice of literacy needs of K-12 (kindergarten to grade 12) students. Now in its sixth edition, the book has been updated to include the latest research findings and instructional practices, new chapters and increased attention to issues such as classrooms as learning communities and the use of digital tools.

More importantly, this book is an invaluable tool for anyone wishing to stay up to date in this rapidly changing field. Its methodology – to rely solely on “evidence-based practice” – will certainly appeal to classroom teachers, administrators and pre-service teachers interested in supporting students’ learning.

Since it was released, tens of thousands of pre-service and in-service teachers have used this text. The content is distilled into flexible strategies for helping a wide array of students succeed. As such, it is broken down in a way to address the major components of literacy, including motivation, assessment, approaches to organising instruction, and more.

Each chapter begins with a bulleted preview of key points, followed by reviews of research evidence. Next, it provides suggested actions for further implementation, including examples from exemplary classrooms. Finally, it employs engagement activities that help teachers apply the knowledge and strategies they’ve learned with their students.

The book is divided into five parts. Part 1, ‘Perspectives on Best Practices’ seeks to establish a particular perspective on literacy and literary instruction. It does this by summarizing the central ideas that run throughout the book, and gives the reader a handle on some of the more radical changes in the literacy space.

Part 2, ‘Best Practices for All Students’ discusses the main questions about literary support for groups of students with particular literacy requirements. ‘Evidence-Based Strategies for Literacy Learning and Teaching’, Part 3, addresses the instructional implications of particular reading processes. It does so in such a way as to present the most recent findings of several wide-ranging studies, as well as analysis.

Part 4, ‘Perspectives on Special Issues’ explores opportunities and issues related to instruction and professional development, including how to address personal skillsets and make improvements outside of the classroom environment. Finally, Part 5, ‘Future Directions’ provides a ref lection on the previous chapters, including further analysis on the role of literacy in the future.

Each chapter also contains a handy content organiser, which covers the major points and additional ‘engagement activities’ to allow both reader and instructor to ref lect upon and apply key concepts and approaches.

The first chapters clarify some of the wider points of literacy that the book makes. The opening chapters are all about ‘Evidence-Based Practices’, and the book identifies and describes ten fundamental instructional practices generally acknowledged to support student literacy development, given today’s increasing demands. Each of these practices revolves around one of two central themes – which run all the way through the book’s five parts – that of “comprehensive literary instruction” and that “teachers are visionary decision makers”.

Firstly, the book seeks to broaden the definition to include literacy in a “personal, intellectual and social nature”. For example, there are instructional implications to things like a student’s independence in using comprehension strategies (and so the text suggests that instructors better use a student’s prior knowledge of literacy comprehension). Correspondingly, it has become vital to understand the increasingly complex role the teacher has in helping a student’s literary development. It does this via ‘evidence-based practices’ and highlights specific examples that might be useful in not just a classroom context, but in students’ lives.

The second part of the book builds upon the first, offering a contemporary definition of literacy. After a comprehensive summary of literacy instruction, it then provides a historical overview of the concept of ‘balance’ between curricula and instruction. This goes back to what was previously discussed (the role of instructors in a student’s life) and suggests providing more educational support over oversimplified literacy instructional approaches. The book suggests solely relying on these sort of approaches actually limits the meaningful direction of teaching – hence it’s proclivity towards the opinion that balance is the way forward.

The middle chapters revolve around best practices in fluency for helping struggling readers. After offering a brief description of the automatic word recognition and prosodic reading processes (both are required for f luency), it lays out six researchbased approaches to better instruction. The specific approaches (reading while listening, paired repeated readings, authentic repeated reading, f luency oriented oral readying, the fluency development lesson and assessing f luency) are presented with both research evidence and classroom implications. Taken together, they provide not just examples to follow but a practical guide for instruction.

Part four further addresses the special issues with regards to literacy, including problems with instruction and professional development. The book uses multiple textual (and some additional media) sources from across grade levels. It describes the research base for multi-source literary instruction, and then provides a number of helpful drivers that depict the various thematic literary approaches. The book then lays out some concrete practices for addressing these issues, focusing on grouping patterns and efficient use of time (for both teachers and students).

Finally, the authors look to the future. In this part the book again reflects on its two key themes, within the broader context of the topics covered, broached and ignored. Specifically, it discusses the questions that have been left unanswered. The final sentence talks of the “hard work ahead” for reading education and literary instruction. It serves as a succinct characterization for the book as a whole.

Best Practices in Literary Instruction i s a n excellent volume filled with best practice literacy instruction. It would make an ideal text for reading educators and curriculum supervisors, as well as any individual looking to further invest in their own literacy instruction.

CURE: A JOURNEY INTO THE SCIENCE OF MIND OVER BODY

Jo Marchant (Crown)

Perhaps we have underestimated the power of placebos. Author Jo Marchant begins her page-turner of a briefing on science’s understanding of the mind’s healing potential with a deep look into the beneficial effects of fake pills, and she comes up with surprise after surprise.

In the US, the effectiveness of placebos in some pain studies has tripled since 1990. In Germany, patients are several times more likely than their counterparts in Brazil to report beneficial effects from placebos. What’s more, such effects also vary depending on the doctor’s body language.

All these wrinkles turn out to be fascinating, and Marchant uses them to argue that patients’ response to medical treatment is shaped by culture, environment and neurochemistry in ways that suggest promising new treatment paths for open-minded doctors everywhere.

Marchant doesn’t stop at placebos, and she proves properly dismissive of some of the claims made for, say, homoeopathy or energy fields. She also readily acknowledges that all mind-based treatments have limits: though the mind can be coaxed into releasing endorphins that reduce pain, and it can perhaps jump-start a patient’s immune system, it has no proven power to shrink a malignant tumour.

But Marchant, a biologist who has been an editor at Nature and New Scientist, does have a “quirky” tendency, when championing hypnosis or some similar treatment, to assume that mainstream medical professionals routinely dismissthe idea that the mind can be a partner in successful outcomes. “That may have been so 50 years ago”, but, with most top medical centres now providing holistic care, “it’s far from true today”.

Many readers will be familiar already with the bulk of the ideas in this book’s second half, said Jennifer Senior in The New York Times. “That stuff about the health benefits of friendship? Again with the mindfulness?” All of that’s been covered extensively by other writers before. But Marchant writes uncommonly well for someone with such a strong grasp of the science, and she has a f lair for tying the researcher’s findings to individual stories. It’s hard not to be moved, for example, when she visits Lourdes, France, late in the book and encounters aff licted pilgrims thriving on the attention they receive in the storied town.

“If there is one lesson to be drawn from Cure, it is this: For the ailing, there is no substitute for face time with someone who cares about your fate.”

BLACK HOLE BLUES AND OTHER SONGS FROM OUTER SPACE

Janna Levin (Knopf)

In Janna Levin’s spectacular book about a landmark scientific discovery, the action begins more than a billion years ago, when two mammoth black holes collided violently, creating a ripple in space that has been expanding outward ever since. But the main story Levin tells, about the researchers who detected the ripple just a few years ago, is even more extraordinary.

Because a handful of scientists committed themselves decades ago to chasing that faint signal – and its proof of the existence of gravitational waves – they heard it when it finally arrived. In “a near-perfect balance of science, storytelling and insight”, Levin has captured the entire tale, and it is hard to imagine that a better narrative will ever be written about the behind-the-scenes heartbreak and hardship that goes with scientific discovery.

MIT-trained theoretical cosmologist Levin threw herself into this story years ago, and she had completed all but the book’s epilogue when Rai Weiss, Kip Thorne and the rest of the team associated with the $1 billion international project announced their discovery.

It could be argued that the author is almost too involved. Once we’ve met Weiss, Thorne and the other major players, Black Hole Blues does tend to draw out. However, it’s worth persevering as Levin, described by critics as “a storyteller of almost Dostoyevskian insight”, weaves a narrative that reveals the scientists to be both heroic and f lawed, and the handful who ultimately triumph seem merely to have been luckier than the many who die or are cast aside before the project reaches fruition.

The discovery that the book describes certainly opened up new possibilities. Researchers had already proved Einstein right in his speculations about the existence of gravitational waves, but the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory – with its 2.5-mile-long detection arms – offers a new way to look back into the universe’s long history. Think about it: Though the collision of the black holes unleashed more energy than any event since the Big Bang, the tiny ripple that LIGO detected amounted to one ten thousandth of the width of a proton. And if human beings are capable of measuring that, they are surely capable of almost anything.