A NOVEL APPROACH

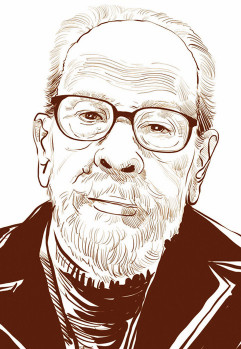

Remembering Naguib Mahfouz, the first Arab writer to win the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Naguib Mahfouz once famously said: “You can tell whether a man is clever by his answers. You can tell whether a man is wise by his questions.”

Throughout his 70-year career, which spanned scores of novels, short stories, films and plays, the acclaimed Egyptian author posed questions about r eligion, politics, g ender roles and nationalism, and sought answers in the everyday occurrences of his beloved Cairo. Today, there’s no debating that Mahfouz – the first Arabic writer to win the Nobel Prize for Literature – was both extremely clever and inherently wise.

The youngest of seven children, Mahfouz was born in 1911 to a devout Muslim family, and spent his early years in al-Gamaliya, a centuriesold quarter in Cairo. It’s the bustling alleyways and characters of this neighbourhood – and Mahfouz’s reaction to the social upheaval of his country, including the Egyptian revolution against British rule in 1919 – that form the backbone of his fiction.

An avid reader from an early age, Mahfouz’s literary influences included Egyptian authors Hafiz Najib, Taha Hussein and Salama Moussa, as well as European greats such as Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Chekhov, Proust, Kafka, Joyce, Faulkner and Shaw. With his vivid depictions of life in the Egyptian capital, critics dubbed him the Dickens of Cairo, with Newsweek saying: “The alleys, the houses, the palaces and mosques and the people who live among them are evoked as vividly in Mahfouz’s work as the streets of London were conjured by Dickens.”

“I read a lot of European novels when I was a young man,” Mahfouz once told journalist Jay Parini of The Guardian. “And I’ve continued to read them. A writer must read. Dickens, of course, was especially important for me,” he said. “The world breaks before you in his books, its light and darkness. Everything is there.”

Mahfouz started writing in primary school, but it wasn’t until after he’d completed a degree in philosophy and begun working as a civil servant that his literary career took shape. In what would be considered a serious ‘side hustle’ in today’s terms, Mahfouz worked in various ministries by day, including as Director of Censorship in the Bureau of Art, and a consultant to the Ministry of Culture, before returning home to write in the evenings, a practice he continued until retiring from civil service in 1971.

He told The Paris Review in 1992: “I was always a government employee. I didn’t make any money from my writing until much later. I published about 80 stories for nothing. On the contrary, I spent on literature – on books and paper.”

Yet this double life did nothing to hinder Mahfouz’s output. In 1939 he published Abath Al-Aqdar (Mockery of the Fates), the first in what he’d planned to write as a series of 30 historical novels. Rhadopis and Kifah Tibah (The Struggle of Thebes) followed in 1943 and 1944 respectively, before he abandoned the past in favour of the present, shifting his focus to the social and political fabric of modern-day Cairo. Over the next four decades, the prodigious writer penned 34 novels, 350 short stories and 25 screenplays. A further 30 of his novels have been adapted into films.

“The Arab world also won the

Nobel with me. I believe that

international doors have opened,

and that from now on, literate

people will consider Arab

literature also. We deserve

that recognition”

NAGUIB MAHFOUZ

“Mahfouz was of massively important influence on Arabic literature; he was our greatest living novelist for a very long time,” said Egyptian novelist Ahdaf Souief. “Mahfouz w as an innovator in the use of the Arabic language; he embodied the whole development of the Arabic novel starting with historical novels in the late 1940s through realism, through experimentalism and so on.”

Today, he is best remembered for The Cairo Trilogy (1956-57). Set in al-Gamaliya and named after real streets from his childhood (Palace Walk, Palace of Desire and Sugar Street), the three books depict the changing fortunes of Cairo through the lens of one family, beginning in 1919, the year of the Egyptian Revolution, and ending in 1944, as the Second World War was coming to a close.

The Cairo Trilogy “deals with the human condition on a large scale,” said Dr Rasheed El Enany, Professor of Arabic and Comparative Literature. “Every human passion and condition is in it: whatever type of person you are, whatever your life experience, it will have something to say to you.”

It was the universality of his themes that captured the attention of the Swedish Academy. In awarding him the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1988, Professor Sture Allén said: “Your rich and complex work invites us to reconsider the fundamental things in life. And the poetic quality of your prose can be felt across the language barrier… forming an Arabian narrative art that applies to all mankind.”

Shortly after receiving the award, Mahfouz said: “The Arab world also won the Nobel with me. I believe that international doors have opened, and that from now on, literate people will consider Arab literature also. We deserve that recognition.”

Prior to winning the prize, only a handful o f Mahfouz’s novels had appeared in the West. Today, Mahfouz’s work has been published in more than 600 editions and 40 languages. “The Nobel Prize has given me, for the first time in my life, the feeling that my literature could be appreciated on an international level. One effect that the Nobel Prize seems to have had is that more Arabic literary works have been translated into other languages,” he said.

Six years later, a botched attack left Mahfouz with nerve damage to his right hand. From then, he couldn’t hold a pen for more than a few minutes a day, and although he continued to dictate his works, his output slowed.

His final major work, a series of stories about the afterlife, was published in 2005. “I wrote The Seventh Heaven because I want to believe something good will happen to me after death,” he told the Associated Press in December 2005. A short time later, in August 2006, Mahfouz passed away. At the time, Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak described him as “a cultural light who brought Arab literature to the world. He expressed the values of enlightenment and tolerance that reject extremism”.

And now, 12 years on, the Nobel laureate’s words speak to us once again. Last year, Egyptian critic Mohamed Shoair discovered a box of unpublished manuscripts at Mahfouz’s daughter’s home, and 18 of these have been released in a collection titled The Whispers of Stars. The publisher, Saqi Books, said: “With Mahfouz’s often ironic, always insightful observation of the human character, this priceless discovery is wonderful news for fans of one of the world’s best-loved novelists.”

NOBEL MUSEUM 2019

Under the title ‘Sharing Worlds’, this year’s Nobel Museum organised by the Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum Knowledge Foundation celebrates the Nobel Prize in Literature. Focusing on the work of selected Nobel laureates in literature, and featuring an interactive exhibition suitable for all ages, the Museum runs from 3 February to 2 March, at La Mer, in Dubai. The Museum is open Sunday to Thursday, 9am – 10pm, and Friday, 2pm – 10pm.